We have already seen that the Aztecs tried to explain celestial phenomena through myths that recount the struggle of the gods—that is, the struggle of the heavenly bodies. This led them to make exact observations, which they recorded on their monuments and in their codices, that are evidence of the advanced stage they had reached in the science of astronomy. It also led them to adopt a calendar, which was undoubtedly the product of the older cultures that had preceded them. Even though it is inferior to the admirable computation made by the Mayas, which is still not surpassed by our present-day system, the Aztec calendar has, none the less, elements that make it an extraordinary scientific development for a people who were, in other fields, very far from the cultural level it indicated.

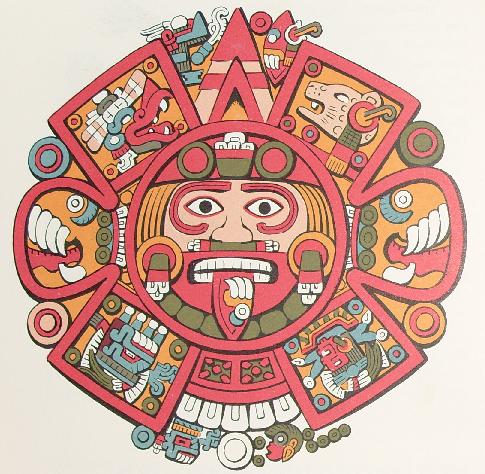

The sun, called Tonatiuh, was invoked by the names of "the shining one," "the beautiful child," "the eagle that soars." He was generally represented by a disk, decorated in Aztec fashion. This disk is widely known because it is an essential part of the celebrated monument called the Aztec Calendar, which is simply a very elaborate representation of the sun.

In the center of the disk is the face of Tonatiuh; at the sides appear his hands, tipped with eagle claws clutching human hearts, for the sun was looked upon by the Aztecs as an eagle. In the morning, as he rose into the sky, he was called Cuauhtlehuanitl, "the eagle who ascends"; in the evening he was called Cuauhtemoc, "the eagle who fell," the name of the last, unfortunate, heroic Aztec emperor.

Around the figure of Tonatiuh there are sculptured in large dimensions the date "4 Earthquake," the day on which the present sun is to be destroyed by earthquakes. In the rectangles of the sign "earthquake" are the dates on which the former suns perished ("4 Jaguar"; "4 Wind," represented by the head of the god Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl; "4 Rain," represented by the head of Tlaloc; "4 Water," represented by a jar of water from which emerges the bust of the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue).

A ring surrounding these figures contains other representations of the signs of the days. Beginning at the top with the head of the alligator Cipactli, the ring closes with the sign for the flower, Xochitl. Then follow the bands with drawings of the solar rays and of jewels of jade or turquoise, for the Aztecs called the sun Xiuhpiltontli, "the turquoise child." They thought of him as the most precious thing in the universe and always pictured him as a jewel. Finally, the two outer bands are the two fire serpents who bear the sun through the sky. Between their fangs appear the faces of the deities who use these serpents as disguises.

These serpents of fire, or xiuhcoatls, that surround the sun also circled the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan and formed the famous coatepantli, or "wall of serpents." Nothing of the latter remains today except a few heads, which are in the National Museum of Mexico. In another temple at Tenayuca, however, such heads can be seen surrounding the temple dedicated to the sun.

Huitzilopochtli fittingly represents the blue sky, or the sky of day, but he is an incarnation of the sun. His struggle with the nocturnal powers led by the moon has already been recounted, and how he must defeat the gods of night each day in order to keep mankind alive and prevent the gods of darkness from destroying the sun. It has also been pointed out that Huitzilopochtli, unlike the majority of the other gods, seems to have occupied a place of importance only among the Aztecs. Indeed, up to the present time, the only representation of this god in any manuscript that comes from a region outside the Tenochtitlan area that has been brought to our attention is the one pointed out by Beyer1 in the Fejervary-Mayer manuscript,2 though the same Mexican god appears to be portrayed in a painting adorning the temples of Tulum, a Mayan city that came under strong Toltec influence.

However, the tribal character of Huitzilopochtli is clearly revealed in the legends of the Aztec migrations preserved in the codices and chronicles and in the foundations of Tenochtitlan.

As a matter of fact, it was Huitzilopochtli who, in the year "One Flint," the year of his birth, induced the leaders of the Aztec tribe to leave their mythical homeland, Aztlan, located in the middle of a lake, and undertake the long wanderings before establishing themselves on another island, also located in the middle of a lake, which would have not only the same physical but also the same mythical conditions as the place from which they had come. During their wanderings Huitzilopochtli was careful to arrange what his people should do; and his spokesmen, who carried his statue, whence came their name, teomama, told the people when they must settle and when they must abandon the places where they had taken up their abode. In this way they spent centuries wandering through the north and central parts of Mexico until they finally settled down in the valley.

Since the god had promised to give his people a definite homeland and dominion over the world, it was necessary for the Aztecs to remain separate from the other indigenous nations, their enemies. This was so necessary that when they were firmly established in the valley and commercial relations and marriages began to break their isolation, the priests were careful to see that a king's daughter who had been given in marriage to an Aztec prince was sacrificed. Hostilities would then break out again, and long-smoldering hatreds would be stirred between the Aztecs and the tribes they were destined to conquer.

But after they left the land of whiteness, they had to establish themselves in a place that was to be revealed by magical manifestations. When the astonished priests found the eagle poised on the cactus, the omen Huitzilopochtli had given them, the trees turned white and the waters became white; there the Aztecs were to found Tenochtitlan. A stream of blue water and another of red gushed forth from the spring, indicating the hieroglyphic atltlachinolli, which means "water, a burned thing," or the holy war which had as its objective the offering of the blood and hearts of the victims to the sun. Metzli, the moon, is also pictured at times with a disk decorated on its outer bands like the solar disk, but generally this disk is black or ash-colored. At the center there appears the figure of a bone twisted into a form resembling a cross section of a small jar of water or the figure of a rabbit, as explained in the legend about the sun, the moon, and the rabbit.

The eagle and the jaguar were the creatures in which the powers of light and darkness were incarnate. Warriors who attained the great honor of being called by these names were more dedicated than others to supplying nourishment to the sun by sacrifice.

The astral gods, being victims of the sun, appear in the codices with their bodies painted with white chalk, striped in red, just as the Aztecs painted the prisoners of war who were to be sacrificed. Facial painting in the form of a black mask marks them as gods of the night.

There were many astral deities, but the most important were Mix-coatl, "the cloud serpent," or the Milky Way; Camaxtle, tutelar god of the Tlaxcaltecans; Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, "the lord of the house of dawn," etc. All the stars, conceived of as gods, were thought to be grouped in two squadrons called Centzon Mimixcoa, "the unnumbered ones from the North," and Centzon Huitzndhuac, "the unnumbered ones from the South." They were the warriors against whom the sun must do battle each day.

But the planets were the tzitzimime, or tzontemoc, "those who fell head first," that is, those who seemed to fall into the west, distinguishing thereby their course of movement from that of the other stars. It is they who, transformed into jaguars on the terrible night at the end of the century, will come down to earth, changed into wild beasts, to devour man.