The idea that man is an indispensable collaborator of the gods, since the latter cannot subsist unless they are nourished, was clearly expressed in the sanguinary cult of Huitzilopochtli, a manifestation of the sun god.

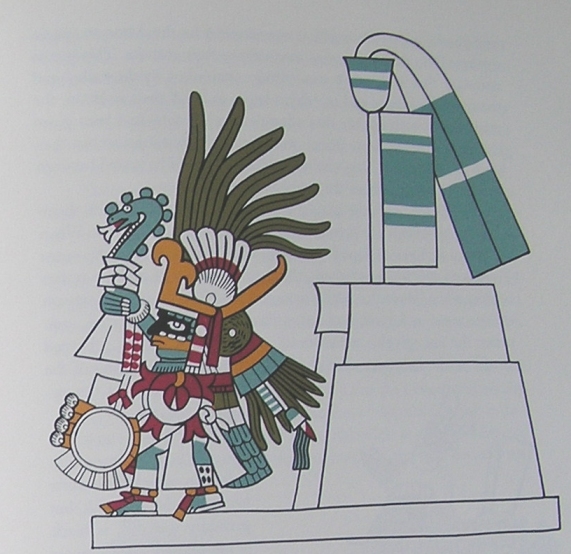

Huitzilopochtli was the sun, the young warrior, born each morning from the womb of the old goddess of the earth and dying again each evening to illuminate with his dying light the world of the dead.

According to legend, Coatlicue, the old goddess of the earth, had become a priestess in the temple, living a life of retreat and chastity after having given birth to the moon and the stars. One day while sweeping, she found a ball of down which she tucked away in her waistband. When she finished her tasks, she looked for the ball of feathers, but it had disappeared. Then she suddenly realized that she was pregnant. When her children, the moon, Coyolxauhqui, and the stars, called Centzonhuitzna-huac, discovered this, they became so furious that they determined to kill their mother.

Coatlicue wept over her approaching death as the moon and the stars armed to kill her, but the prodigy in her womb spoke to her and consoled her, saying that when the time came, he would defend her against all.

Just as her enemies came to slay the mother, Huitzilopochtli was born, and with the aid of the serpent of fire, the sun's ray, he cut off Co-yolxauhqui's head and put the Centzonhuitznahuac to flight.

So it was that when the god was born he had to open combat with his brothers, the stars, and his sister, the moon; and armed with the serpent of fire, he puts them to flight every day, his victory signifying a new day of life for men. When he consummates his victory, he is carried in a litter into the center of the sky by the spirits of warriors who have died in combat or on the sacrificial stone. When afternoon begins, he is picked up by the spirits of women who have died in childbirth, for they are equal to warriors because they, too, died taking a man prisoner—the newborn child. During the afternoon the souls of the mothers lead the sun to its setting, where the stars die and where the sun, like the eagle in his fall to death, is gathered close again by the earth. Each day this divine combat is begun anew, but in order for the sun to triumph, he must be strong and vigorous, for he has to fight against the unnumbered stars of the North and the South and frighten them all oft with his arrows of light. For that reason man must give nourishment to the sun. Since the sun is a god, he disdains the coarse foods of mortals and can only be kept alive by life itself, by the magic substance that is found in the blood of man, the chalchihuatl, "the precious liquid," the terrible nectar with which the gods are fed.

The Aztecs, the people of Huitzilopochtli, were the chosen people of the sun. They were charged with the duty of supplying him with food. For that reason war was a form of worship and a necessary activity that led them to establish the Xochiyaoyotl, or "flowery war." Its purpose, unlike that of wars of conquest, was not to gain new territories nor to exact tribute from conquered peoples, but rather to take prisoners for sacrifice to the sun. The Aztec was a man of the people chosen by the sun. He was the servant of the sun and consequently must be, above everything else, a warrior. He must prepare himself from birth for his most constant activity, the Sacred War, which was a kind of tournament in which the enemies "of the house," the Tlaxcaltecans, were the special challengers. They were the men who wore the lip plug curved in the form of a claw and, adorned like the Aztecs in their best finery, displayed great panaches of rich feathers and armor, and standards and shields sumptuously adorned with feather mosaic work and precious stones, copper plates, and golden bells.